- Hans Holbein "Ambassadors"

- Hans Holbein Paintings

- 6 August '19

by Alexandra Osadkova

6 August '19Hans Holbein "Ambassadors"

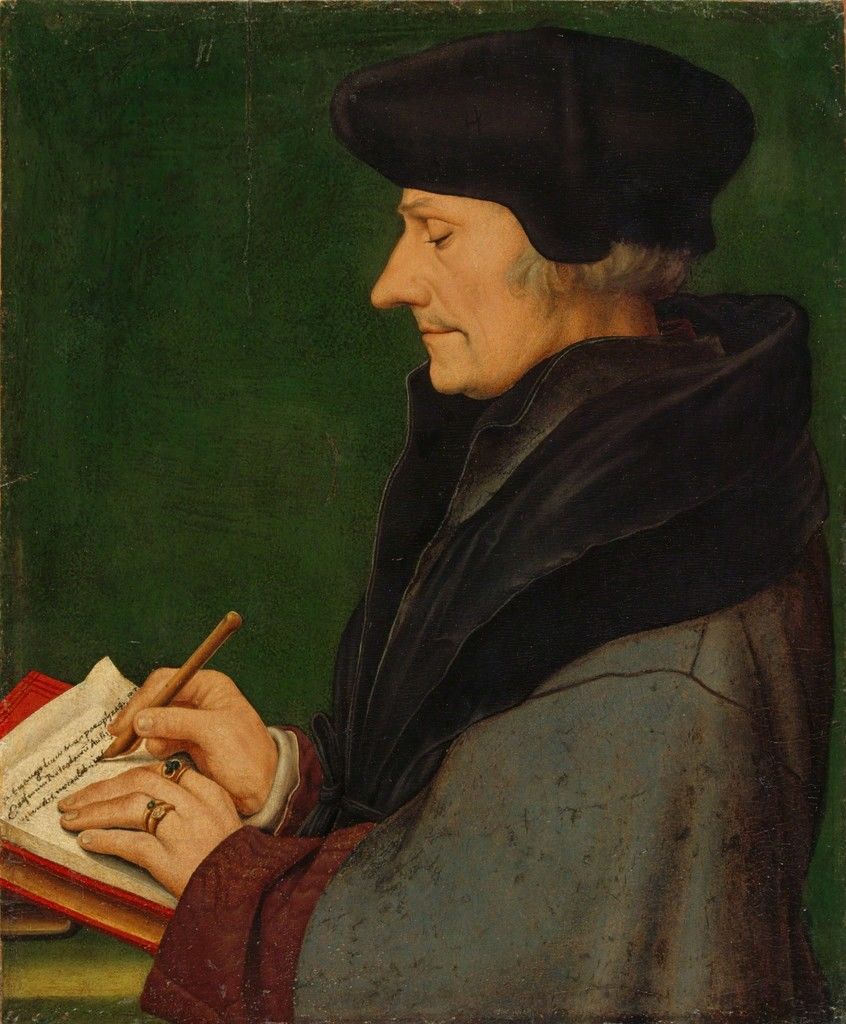

Now's an obsession with the deadly court of King Henry VIII wouldn't exist without the artistic abilities of a few men. Hans Holbein the Younger, a German artist and official painter to the king, brought the Tudor era to life through over 100 portraits which masterfully captured the individual expressions of his subjects including Thomas More, Thomas Cromwell, King Henry, and lots of his six wives. Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve, also called The Ambassadors, has been heavily scrutinized by countless historians. The dual portrait, proudly exhibited at London's National Gallery, remains a fascinating enigma in which every detail appears to suggest several meanings. To start the hopeless task of decoding this almost life-size work, an individual must first endeavour to comprehend the dangerously political universe that Holbein inhabited, and his complex biography.

Henry VIII quarrelled with the Pope within the Catholic Church's refusal to give him the divorce from his wife. He went ahead and married Anne Boleyn, and shortly after he celebrated the birth of their daughter (half-heartedly, as he had hoped for a boy ): the future Queen Elizabeth I. Henry's split from the Church was imminent; just a year later, the headstrong king could break from Rome and set himself as the head of the Church of England. Many blamed Boleyn for magic Henry and consequently causing the schism. Before his appointment in the king's court, the artist had established a reputation in his native Germany for spiritual paintings (his father was the renowned Late Gothic painter Hans Holbein the Elder); and in Basel, Switzerland, he was famous for woodcut illustrations. Until arrival in England, the artist had hardly ever dabbled in secular portraiture, a new type of painting to have emerged in the Northern Renaissance. Somehow, his prior activities and affiliations did not arouse suspicion in the English court; Holbein retained the king's favour before his passing. Henry's actions in breaking away from the Church, motivated mainly by his desperation to make an heir, threw a wrench into Europe's already shaky political and spiritual order. Henry's break from the Church opened the door for Reformation and humanist idea to enter England, the characteristics of that would eventually change much of the continent.

His modestly dressed friend Georges de Selve, a cleric and intermittent diplomat (shortly to be consecrated Bishop of Levaur, France), stands on the right side of this painting. He might have been in London on a similar company. Because of this, both of these ambassadors found themselves in a helpless place, witnessing events unfold they were not able to influence. Nevertheless, this painting manages to redeem their plight, contextualizing the politics of the day within a philosophical and spiritual framework with a single unifying theme: the Renaissance concept that established guy in the central place of creation, uniquely engaged with both the earthly and heavenly realms. The"Macrocosmic archetype," a personal Renaissance philosophy that permeated many areas including astrology, alchemy, and geometry, posits that the forces that regulate the human body are just like those that shape the whole universe. Therefore, a person comprises a miniature cosmos or microcosm. Even if Dinteville and de Selve were unaware of the inscription, they likely would have understood the floor layout signified this idea. The region of the painting which has long captured the imagination of most historians, however, is the astonishing assortment of cutting-edge technological instruments, modern mathematical treatises, and musical scores from the period played out between the two figures. Believe it or not, there's a precise logic to this melange of intriguing clues, which reveal intellectual as opposed to monetary wealth.

Peter Apian's New and Dependable Instruction Book of Calculation for Merchants provides subtext beneath it. A ruler opens the textbook to a page of equations, beginning with the term dividirt, meaning "let branch be made," an apparent reference to the spiritual schism tearing Europe apart. In another natural movement, the lute's broken series symbolizes ecclesiastical discord. The fantasy of reconciliation expressed within this little detail, of course, would never materialize. Though the objects talk to the futility of their ambassadors' diplomatic and spiritual objectives, they don't appear downcast. As the film shows, there are other, more significant powers in the workplace: death and God's ultimate salvation. While these items show Holbein's skill in depicting complex three-dimensional objects, their exact realism has metaphysical meaning, too. The tactile renderings of lace, fur, wood, and metal draw the viewer's eye to the material presence of the painting, aligning it with fact, instead of religion or allegory. Holbein also reminds audiences of the subjects' humanity, even as the picture immortalizes them.

The Ambassadors' most important deathly hint is the unmissable anamorphic skull which stretches across the painting's bottom centre. While its skewed perspective leaves the skull mostly unreadable when seen straight-on, Dinteville might have initially positioned this job with a door in his chateau, so that a viewer walking past in the side would be faced with the smiling face of death. At its simplest level, the skull represents a memento mori (literally"remember thou shalt die"), a reminder of man's inevitable mortality and a way to urge viewers to reject earthly temptations. But its distortion here indicates other symbolic readings. The skull metaphorically obscures the middle of the world as it (literally) covers the centre circle on the ground pattern. Additionally, the perspectival experiment draws attention to the limitations of human vision and compels audiences to question their place in the world.

But, since the painting counters, patrons and audiences alike shouldn't fear death. There in the upper left-hand corner, partly hidden by the emerald green background, a crucifix stands for revival --God's promise of eternal life for the faithful. (Christ's salvation can be alluded to in the cylindrical sundial, which can be set to April 11th, the date of Good Friday at 1533.) Since scholar Kate Bomford has contended, Holbein's portrait, by serving as a"mirror of mortality," secures a way of eternal fame for its sitters, in addition to salvation, merited by their virtuous friendship. For all its focus on materiality and logical structure, logos, and optical tricks, the real subject matter of this Ambassadors is the unrepresentable and unknowable--God.